Arnold Ageta

There is a growing and intense debate on whether human security risks related to climate change could become the hard security threats of tomorrow.

According to the report launched by the UNDP, the impact of climate change in Africa is exacerbating conflict dynamics in several hotspots across the continent.

‘‘The conflict increases competition over natural resources while degrading ecosystems and landscapes,’’ read the report.

The report cites climate change as one affecting job opportunities, transhumance and settlement patterns.

The report further says while climate impacts do not necessarily cause violent conflict directly, there is growing evidence that a changing climate intensifies tensions between and within communities and states.

One of the most vulnerable regions to climate change and variability is the Horn of Africa which has been hit by slow and sudden onset disasters including droughts, floods, locust invasions, fresh water salination along the coast, and rising sea levels, threatening livelihoods, food and water security and ecosystems.

The region also faces historical conflicts around territory, resources, or ethnic lines, which are now compounded by climate change and the pressure of a bulging youth population with inadequate economic opportunities.

The report sought to fill a gap in multidisciplinary programs that are responding to the interlinked nature of climate, peace, and security in the Horn of Africa.

UNDP and Life and Peace Institute, working under the UN Climate Security Mechanism, have designed this survey dubbed ‘Mapping of Climate Security Adaptations at Community Level in the Horn of Africa’ with a special focus on Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia.

The report findings indicates that challenges facing all stakeholders in addressing climate security are severe in terms of the speed of change that is now being experienced by communities.

In addition, according to the report, the conflation of challenges that arise from the macro trends (such as population and environmental impacts) affecting the different localities visited, in conjunction with climate change, compounds the challenges being faced by communities on the ground.

There are, however, ongoing efforts and approaches being adopted by the government and civil society actors at community level which show some promise in their locality, can be built on and developed further.

An interesting finding was that all of the different adaptations that were identified had all been introduced either by civil society and NGOs or by government.

Adaptations (aside from negative coping mechanisms) that were solely community-devised, home-grown and initiated were not encountered in any of the locations researched.

It is important to note that all of the areas selected for research are located within existing conflict systems and ongoing conflict dynamics, and in the case of the Karamoja, a cross-border conflict system.

This has affected the breadth with which potential climate security adaptations have been interpreted.

UNDP/CSM differentiates between a focus on climate change adaptations (adaptation and mitigation) and climate security adaptations with the latter specifically focusing on peace and security.

However, in the majority of areas visited, the distinction appears somewhat artificial as changes in any of the key dimensions (environment, governance, macro trends, and resilience) can all potentially affect the existing conflict dynamics or indeed induce new conflicts.

The report demonstrated that security is currently critical factor in the Karamoja playing into and affecting both intercommunity conflict dynamics and as criminal activity. Young men are engaging in raids on kraals to steal household livestock and food.

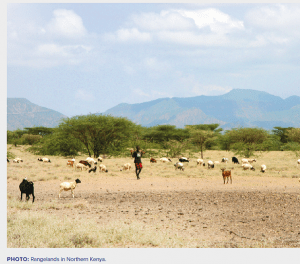

Livestock raiding in pastoralist and agro-pastoralist communities has cultural roots, and was previously clan-based (i.e. between clans within the Karamjong) or inter-tribal (e.g., between a clan of the Karamajong and the Pokot or Turkana), in this context.

For a variety of reasons this conflict pattern has changed but contributing factors include unemployment, the loss of pastoralism as a primary livelihood, increasing reliance on household or rainfed agriculture, unpredictable weather and therefore food security.

A fundamental challenge in addressing climate security in the region is how best to manage complexity. This can result in tensions between differing system needs, approaches and timeframes to achieve effective results.

Biodiversity has reportedly declined, and productivity of the resource base has also been reduced.

‘‘Respondents noted that rangelands in Karamoja and Laikipia are not as productive for pastoralism, or beekeeping and productivity of forest areas in terms of Non-Forest Timber Products (NFTPs) in Majang (Ethiopia) and the Shimba Hills and along the coast (Kenya) has declined,’’ indicated the report.

‘‘Respondents noted that rangelands in Karamoja and Laikipia are not as productive for pastoralism, or beekeeping and productivity of forest areas in terms of Non-Forest Timber Products (NFTPs) in Majang (Ethiopia) and the Shimba Hills and along the coast (Kenya) has declined,’’ indicated the report.

These changes are a result of human activity associated with trends in movement, population expansion and changing behaviours, in conjunction with the effects and impacts of altered weather patterns and events.

Despite generally not understanding the specific causes of global warming and climate change, in each location, people linked their personal experiences with environmental degradation and changing weather patterns.

The report read: ‘‘The impacts of these changes are profound, as marginal lands or natural resources in some locations may no longer be viable or predictable in terms of their use and are increasingly vulnerable to overuse that could lead to a level of degradation rendering them unusable in the near and medium-term future.’’

The report shows that along the Kenyan coast where the use of the adaptation ‘tengefus’ (community marine conservation areas) is common, informed respondents noted that the coastal waters are being overfished by a combination of local fishermen as well as increasing numbers of fishermen from Tanzania.

‘‘The fisheries are simultaneously being damaged and altered through increased frequency of storms, changing sea levels and warming of waters,’’ the report reads in part.

In Karamoja, according to the report, consequences of increased temperatures include increased evaporation of water from land resulting in hardening and the drying up of wetlands and marshy areas (also increasing the impact of herds on sensitive pastureland).

The land is also unable to absorb rain when hard and when rainfall is no longer soft and falling over long periods of time because of hardened land.

Some of the respondent who were interviewed also attributed the outbreak of pests and diseases to increased temperatures in the Karamoja – in particular the Tsetse fly (a vector for Trypanosomiasis), and army worms (which affect most crops but in particular maize).

On the other hand, environmental degradation and temperature increases are also significantly affecting wildlife.

‘‘Animals previously common in an area are increasingly struggling to survive due to insufficient food, lack of water and other habitat changes. This was stark in Gambella National Park where some animals are no longer seen due to drying of wetlands,’’ indicates the report.

On the Kenyan coast, some species of fish were reported no longer to be found in the shallow water. As water temperature has risen, so they migrate to cooler, deeper water.

Impacts on insects and other parts of ecosystems were not reported or were less clear unless a disease was associated with the change, for example, the prevalence of Tsetse fly or army worm and other diseases.

An interesting finding of this research is that locations where indigenous cultures remain socially very strong; the natural environment was in a (relatively) better condition compared to similar locations where cultures have weakened. Tepeth and Pokot societies in Uganda are living in well forested areas and fiercely adhere to traditional resource management practices.

Several respondents noted the importance of understanding that livelihoods and ways of life in vulnerable areas such as semi-arid and arid lands have developed because they are the most appropriate, sustainable and suited to that particular environment.

For instance, there is a body of evidence to show that the way that pastoralism is practiced across many parts of the African continent is far more productive and more sustainable than ‘modern’ ranching systems that dominate in countries like Australia and the USA.

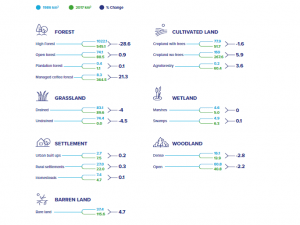

Land use changes have been significantly influenced by climate change and change climate security dynamics which are foreseen to worsen in the near future.

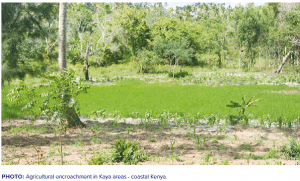

Drying wetlands are increasingly being encroached on and used for agriculture (e.g., in Gambella, Karamoja, and Kenyan coastal areas that are considered Kaya shrines), which is reducing carbon sequestering locations, increasing uncontrolled flooding and reducing wildlife as well as options for dry season grazing, affecting conflict between pastoralists and farmers.

Deforestation for settlement, agricultural and commercial crop growing impacts other land at the location and in more distant places.

Changing pastoralist migration patterns due to economic development initiatives, or extractives, blocking transhumance routes, changing land use and increasing agriculture, commercial investment, encroachment into grazing corridors, failed livelihoods have resulted in rural to urban migration.

Another key area to note in the report is the movement of tribes into previously non-traditional areas seeking resources like herders from Ijara in Northeastern Kenya moving towards Taita Taveta and Tana River. Scarcity of resources particularly water and firewood around inter-county border areas or other locations such as the coast – Kilifi and Taita water basin and Mombasa.

Also affected by land use practices and climate change is pastoralism throughout the region. A somewhat counter-intuitive example noted is that pastoral conflict increasingly occurs in locations where there are relatively richer resources.

During drought, pastoralists are scattered looking for pasture. When rain occurs people gravitate with their livestock and thus encounter each other, resulting in an increase in the risk of conflict.

In Laikipia and Marsabit this relationship is used by the Northern Rangelands Trust to inform their early warning mechanisms and try to prevent events predicted by rainfall.

‘‘Land use issues that are creating and exacerbating conflict are being enabled, in some cases, by governmental policies, politicians’ lack of understanding of climate security, and political will,’’ the report indicates.

The linkages between conflict and climate change may not be immediately clear as they may be masked by other factors such as identity and historical grievances.

‘‘In Karamoja, Laikipia, Gambella and South Omo, the report says, the roles that young men may play within a broader interpretation of warrior culture affects their response to various situations.

While social patterns across Karamoja are broadly similar, this is not always the case. It was noted that some clans, such as the Pian do not really engage in conflict, even if they are attacked or are victims of raids. In Laikipia there are also cultural dynamics among and between group influencing behaviours.

Conflict does not necessarily occur in the place of environmental strain being affected by climate change.

‘‘This emphasises the challenge that most people in the region do not understand how different parts of the environment are impacting others. This is clearly the case for the Turkana when they cross from Kenya into Uganda,’’ stated the report.

There is increasing interest in the inverse relationship between conflict and climate change. Where the consequences of conflicts have a significant impact on climate change. These were not so apparent in the research. It is sometimes assumed that war and conflict usually reduce and impede economic development and thus emissions.

The study demonstrates that the challenges facing all stakeholders in addressing climate security are severe in terms of the speed of change that is now being experienced by communities.

In addition, the conflation of challenges that arise from the macro trends affecting the different localities visited in conjunction with climate change compounds the challenges being faced by communities on the ground.

There are, however, ongoing efforts and approaches being adopted by government and civil society actors at community level that can be built on and developed further which show some promise in their locality.

A fundamental tension in addressing climate security in the region is the need to break down problems into their constituent parts and support immediate while also addressing the integrated and interconnected nature of the different factors at sufficient scale and with an understanding of the appropriate long-term timeframes needed for effective interventions.

The report recommends developing and modelling cross-sectoral and multi-stakeholder approaches with different institutions and sectors that address climate security issues holistically incorporating components that tackle the three most important dimensions; resilience, environment and conflict in an integrated manner.

One thought on “Human security risks related to climate change in the Horn of Africa”